It was one of those defining moments that occasionally punctuate our working lives. The realisation that what had been previously taken as an article of faith was, in fact, the cause of the problem. As this inconvenient truth dawned on the faces of the assembled transformation leaders, there was a perceptible shift of energy. Feelings of release, as well as fear pervaded the hotel conference room in which we were gathered. ‘We have been trying to project manage the Operating Companies into submission, expecting them to eat the sausages’, explained one of the leaders, ‘when we should have been engaging them in the transformation by listening to their needs and treating them as equals’. It was one of those revelations that sound remarkably simple in the retrospective telling, but unbelievably challenging to grasp when you are living through the experience in real-time. ‘Life’, observed Soren Kierkegaard, ‘can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards’.

A tale of thwarted transformation

This is a tale about when things don’t go to plan[i]. That makes it unusual content for the self-congratulatory world of business media. It is even more unusual for LinkedIn, a forum which tends to invite self-promotion, where stories of hero consultants and business leaders claiming to have turned round the fortunes of companies through their flawless execution of well laid strategies, are pervasive. Of course, we all know that strategies, programmes, projects, and so on, never go to plan. There’s always an element of (often extensive) improvisation and, more than we’d like to admit, a multitude of unintended consequences. It’s just that the prevailing orthodoxy has us believe that methodically following a linear, planned sequence of steps is the best way of achieving our goals. We find this surprising, given that military doctrine has long since followed the philosophy ‘no plan survives first contact with the enemy’[ii], but equally surprising that we allowed ourselves to be caught up in the prevailing orthodoxy. As regards LinkedIn, too many of us won’t admit our plans went awry for fear of tarnishing our professional reputation in an aggressively competitive market. Sadly, this means less learning for everyone because, by and large, we learn a great deal more from reflecting on our mistakes than from crowing about our successes, imagined or otherwise. It is in the spirit of increasing this learning that we share our story of thwarted transformation. While we do this with some trepidation, we believe our experience is typical of most one shot, big bang transformations.

The story in a nutshell

We were recruited in 2016 by an international telecommunications and technology company to lead the start-up of a shared services operation at the heart of a global transformation. We subsequently discovered the transformation had become profoundly stuck. The C suite’s belief that there was broad agreement to the transformation proved to be ungrounded. In December that year we convened a conference of the key senior stakeholders involved – global leadership and the operating companies met with the programme team and our strategic implementation partner – with the aim of breaking through the deadlock. Our aim was to create the conditions in which a moment of truth conversation could happen. And, as the account above shows, we succeeded. The programme regained momentum and for a while it looked as if we had navigated our way out of an impossible impasse. But ultimately there were too many constraints. The top down, waterfall way in which the programme had been framed, predetermined deliverables, the change by diktat approach adopted by HQ, and the intransigence of key senior stakeholders, proved impossible to escape.

How we became involved

This wasn’t exactly our first rodeo. We had been leading transformations for almost two decades. Akos had spent most of his career in senior BPO operational leadership roles with players like GENPACT and WNS; Tim’s career had focused on the people side of change in senior HR roles with PwC, a mega Dow/Aramco start-up, and in consulting assignments with technology and services organisations across EMEA. Both of us had enjoyed predominantly successful careers in business transformation, working with blue-chip companies.

Undoubtedly, we were swept away by the telco’s grandiose ambition of transforming itself into a digital technology company within three years. Here was a big, bold vision, that resonated with our (on reflection, hubristic) social identities of changing the world. A renowned strategy consulting firm had been hired the previous year to develop a new global operating model to drastically improve efficiency and globalise the organisation. At the heart of this new model was a Global Shared Services operation that centralised back-office operations across multiple functions, with the aim of increasing transparency and effectiveness. Support functions in the operating companies were required to relinquish responsibility for their transactional activities and transfer them into shared service centres located in Eastern Europe, Russia and South Asia. The functional leaders in the operating companies (CFOs, HR Directors and so on) were to become business partners, increasing their focus on the commercial goals of the organisation.

Transforming without changing

And yet, for all the talk of transformation, there was little evidence of a change process that sought to engage those impacted or considered the broader consequences on their roles and the wider organisation. The operating companies were expected to let go of activities on which they relied to run their business effectively; support function leaders compelled to take on a new role that few were capable of performing. Despite the seismic change of mindset and capabilities required, the notion of involving the operating companies in shaping the transformation was dismissed as folly. The executive team was adamant that key stakeholders had bought into their vision. It was deemed unnecessary and unhelpful to pay additional attention to their needs and agenda. As a result, the management of change became little more than a communications exercise and the ‘transformation’ a series of previously agreed project milestones to be followed sequentially to achieve the required outcome.

Over the years we’ve learnt to question what’s really going on when bright people start doing foolish things. The executive team was composed of very talented individuals with vast amounts of telco and transformation experience. What was driving their apparent intransigence and adoption of a top-down approach? We understand it as a response to what was happening in their world. The company had recently suffered a near-lethal corruption scandal which created a pressing and urgent need for radical change – in particular, greater transparency in back-office financial transactions. Addressing such a challenge in an emerging market environment was challenging enough, but it was made infinitely more difficult by a hyper activist majority shareholder who regularly intervened in the operational running of the business, causing it to bounce from one direction to another. Faced with overwhelming complexity and the pressure to act quickly, one can understand the members of the executive team decided to push on grimly, even if they harboured misgivings individually.

Taking leadership of the change

As a consequence, we found ourselves in the invidious position of implementing a project decreed by the top with little engagement of those it would impact. Had the culture of the organisation been characterised by obedience and deference to authority, this might have worked. In reality, the organisation was a loose federation of operating companies each with its own strongly independent executive team, some more closely connected to the majority shareholder than the corporate centre. Most were unfamiliar with a shared services approach and fearful of losing control of activities on which they were dependent to achieve results. The operating companies were, therefore, highly resistant to being simply told to ‘eat the sausages’.

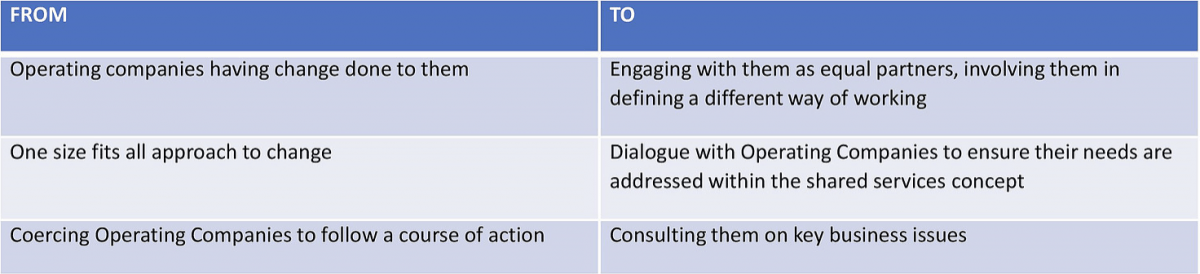

In the circumstances, we decided to do two things. First, we challenged the executive team on the feasibility of their plans and tried to engage them in further dialogue with the operating companies. This met with limited success due to the unwillingness of the C suite to consider alternatives to the previously agreed strategy. Next, we convened the conference that we referred to at the beginning of this article to trigger a breakthrough conversation. At this point, people’s understanding of the broader change required began to crystallise. In the absence of leadership from the corporate centre, the programme team assumed the leadership of the overall change process, defining it as:

Wrestling with newfound responsibilities

The creative energy released by the December conference led to the reframing of the change management proposition and the development of more effective and consultative ways of engaging with the operating companies. There was broad agreement that our approach to change had been fragmented and transactional, rather than systemic and inter-connected. It had amounted to little more than communication during the execution phase of the project. The engagement of local companies prior to execution had been uncoordinated and ineffectual and the ongoing support of the change process post execution woefully lacking. Worse still, many of the operating companies were alienated by the suggestion that their businesses were substandard and needed to be ‘fixed’ through the imposition of a shared services model.

The new change proposition mapped out a consultative process several months ahead of project kick-off in each country, with the aim of building trust and giving the operating companies a chance to shape the change process. This was led by newly appointed relationship partners focused on building and sustaining the relationship with the local businesses, navigating internal politics and providing strategic consulting to senior leaders on the change management of the transformation. The new approach was rolled out in several of the companies and the programme adapted to address local needs. Engagement levels rose and commitment to the transformation increased significantly.

Yet, despite our best efforts, underlying systemic issues led to the programme’s undoing. Ultimately, the global transformation was a solution in search of a problem. It had the glitzy packaging of the world’s top strategy consulting firm and an impressively well-crafted business case that referenced global best practice, but when you dug beneath the surface it was, in the words of Macbeth, ‘…full of sound and fury, signifying nothing’[iii]. Little attention had been given to the context of the organisation, in particular, the independent nature of the local companies, or the maturity of the markets in which they were operating. As a result, unrealistic assumptions were made about support for the transformation and the speed with which it could be achieved. When it came down to it, most local leadership teams saw the whole thing as little more than a power game with the corporate centre. For them, it was an attempt to shift the balance of power in favour of the centre by devaluing their business assets and reducing their influence. Politically, the organisation was simply not ready to adopt a globally integrated operating model.

We referred earlier to challenging the executive team on the feasibility of their plans. While spirited, this stopped short of fundamentally questioning the purpose of the transformation and the creation of a shared services organisation. We did not embark on an exploration of the underlying issues that the transformation was addressing. We went along with the plan given us. Why did we not press harder? Like everyone else in the organisation, we were affected by a leadership culture characterised by fear. Simply put, it did not feel safe to challenge upwards very robustly. There was a very real possibility of being bullied by a member of the senior leadership team. In such an environment it is incredibly difficult to step back and question at a systemic level.

As well as these systemic issues there were some of our own making. The programme team struggled to let go of their identity as implementers and expert fixers and embrace the different mindset required by the new change proposition. Some defaulted to old, unproductive patterns by referring to the local companies in macho, demeaning ways, or favouring technical content over relationship, or continuing to sell the shared services concept as opposed to addressing local needs.

Learning to be a reflective leader of transformation

The learning from this experience of thwarted transformation has been profound. It has taught us what it takes to become a reflective leader in charge, though not necessarily in control, of organisational change. We highlight four areas of this learning we believe critical for the leaders of transformation.

Before embarking on the transformation journey, inquire as to the intention behind it. This means exploring just how realistic and feasible the transformation really is (as opposed to utopian or idealistic) and the degree to which it considers the context of the organisation. It means having uncomfortable conversations with senior leaders and questioning what’s going on. This can be risky, especially in cultures that expect compliance, but the consequences of not doing so – ethically and personally – are often far-reaching. Most transformations have profound consequences for people’s working lives and their social identities. Whole workforces and communities may be displaced, jobs lost, social capital disrupted, new work created without the same pay or cachet as the old work. For those on the receiving end, transformations are often experienced as cruel, callously implemented by people doggedly pursuing the transformation project plan without asking questions about the consequences for others or the organisation as a whole. Equally importantly, interrogate your motives for participating in the transformation. The excitement and adrenalin rush of an enterprise-wide change programme is often seductive for the leader, particularly if it is tied to a utopian vision. Have you been taken in by the glamour of it all?

Find ways to critically reflect with others on the direction the change journey is taking. As the African proverb goes, ‘A fish is the last to discover water’. Once onboard the roller coaster of transformation it is easy to get sucked into events and fail to find the time to stand back, slow down and make sense of what’s really going on. In our experience ‘slowing down’ means creating the conditions in which people can:

- Express uncertainty and doubt about the change process. Many leaders overstress the importance of alignment, in our opinion, with the consequence that anyone expressing doubt is perceived as not getting on board the change train. Transformations touch people’s working lives and identities in deep ways that inevitably provoke strong emotions. Leaders of transformations play a vital role in legitimising those emotions including the expression of uncertainty and scepticism. Paying attention to your own and other people’s misgivings may alert you to ways in which the change process is failing.

- Pay attention to the dominant metaphors used to describe the transformation as well as the way the transformation team talks about those impacted by the change. ‘Words create worlds’[iv] – they frame the way people truly see the transformation, often at a subconscious level. ‘Most transformations are underpinned by a metaphor that informs what the transformation means to people. This metaphor, and the language that brings it to life, either creates a sense of opportunity and possibility, or generates fear, anxiety and compliance’.[v] For us, the metaphor coined by a member of the executive team of making the operating companies ‘eat the sausages’ revealed the true nature of the transformation and determined the way they subsequently responded. Equally, the way the programme team talks about those impacted by the change will shape the relationship between the two.

- Recognise when roles and identities need to be reframed in order to keep the transformation on track. In our case, the situation required the transformation team to stop seeing themselves as either expert fixers or corporate saviours and instead take on the role of organisational consultant and provocateur.

- Challenge rigidly held beliefs and ideologies that do not address the organisational context and the shifting nature of the transformation journey. We were constrained by a specific ideology of shared services that became cult-like, was not evidence-based nor relevant to the context and challenges faced by the organisation. Ideologies are viral, infecting conversation to the degree that it becomes impossible to challenge them or come up with anything other than a binary response (for or against). The Brexit crisis in the UK is an example of what happens when this pathology infects the national dialogue.

- Grow your relationship with implementation partners into a strategic alliance and away from a client/vendor transaction. Creating trust and closeness in these relationships enables the programme team to navigate the inevitable uncertainty and lack of agreement inherent in major transformation. This is difficult to achieve because consultancies have their own agendas and clients are quick to blame the consultancy when things go ‘wrong’, which they inevitably will. But in our experience, building strong interpersonal relationships and a sense of ‘tribe’, creates a partnership that sustains the team during moments of crisis. The ‘importance of underscoring our shared humanity’ and retaining ‘focus on the things that unite us’[vi] is for us, one of the defining attributes of successful transformation leaders and their teams.

Listen to many different voices, particularly voices from the edges of the organisation, rather than the centre. Convening conversations with those not aligned to the central informing ideology underpinning the transformation elicits information about the real, underlying issues and generates innovative thinking about how to address them. It is also a useful way of grounding the transformation effort, ensuring it is addressing real, rather than imagined, business needs.

Pay attention to the impact transformation has on people’s identities and the relationships between them. We believe transformation leaders should have responsibility for job design and change management in both the retained organisation (the area of the business from which jobs and processes may be removed, but which continues albeit in a reconfigured form) as well as in the transitioned (newly created) one. Responsibility for these things in the retained organisation will of course be shared with local leaders, but without this it is difficult to influence the reconfiguring of relationships and identities necessary to make the transformation a success. Had we been able to influence the conditions in which people’s professional identities were formed in the operating companies, we might have helped them to better accept the change. To paraphrase an observation by Chris Mowles, ‘If change processes radically reconfigure sets of relationships, then paying attention to’ how relationships are being ruptured, giving people an opportunity to express their sense of loss, supporting them in reknitting, repairing and developing a renewed sense of purpose and belonging, ‘is at the heart of what a manager of organisational change is doing’[vii]. Really effective leadership of transformation requires paying full attention to these social and relational processes, as opposed to simplistically following a linear, mechanistic project plan.

Becoming a reflective team in charge of transformation

We started this article by recounting a moment of collective realisation on our journey of transformation. This came about as a result of bringing a diverse group of actors together, expressing doubt about the transformation, reflecting on what was, and what was not working and listening intently to each other – in other words many of the things we have summarised above. As a programme leadership team, we were unable to hold this new way of working for long, but the generative impact of becoming a reflective team in charge of transformation continues to shape our professional work with organisations, as well as personally.

[i] Morris, I, July 20 2018, ‘When Transformation Goes Bad’, Light Reading

[ii] Ministry of Defence, UK, May 2011, ‘Army Doctrine Primer’

[iii] Shakespeare, W, 1606, ‘The Tragedy of Macbeth’

[iv] Barrett, S and Fry, R, 2005, ‘Appreciative Inquiry: A positive approach to cooperative capacity’, Taos Institute Publications

[v] Metalogue Change Consultants, December 2018, ‘Organisation Transformation: Fateful Framings’

[vi] Junger, S, 2016, ‘Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging’, Twelve

[vii] Mowles, C, September 21 2018, ‘What leaders talk about when they talk about transformation’, Complexity and Management Centre blog