Everything old is new again. ‘Digital nomads’, ‘gig workers’, ‘remote workers’, ‘working from home’, and ‘distributed teams’ are modern buzzwords in the world of work, but the underlying practices are timeworn. Only some of the enabling mechanisms and technologies, are new.

Nomadism and remote teams

Like many working for technology or global companies, or as a member of global project teams, my experience of remote working and distributed teams, including working from home, started in the 1980s. But it’s hardly a 20th century phenomena, from c. 1700 – 1380 B.C.E Minoan traders had established outposts, from Spain in the west, to Egypt in the east.

Traveling through the vastness of Mongolia in 2007, I learnt about transhumance, the seasonal movement of families and their livestock twice a year, between summer and winter locations. Reliant on strangers providing food and shelter for people and their herds during their journeys, in a country that ‘make their own roads’. With very few established roads existing outside of the capital, and the famous Silk Road.

This centuries old form of pastoralism enabled by distributed coordination and cooperation, helped me make sense of why the Mongols in the space of one lifetime, created the largest contiguous land empire in the history of the world. History records the Mongols as leaving a trail of death, destruction and misery behind them, but also of Genghis Khan as a leader, exceptional in galvanising diverse, restless and disparate tribes, over huge distances. They were united by a codifying set of laws.

Working from home and self-organised workers

In 1983 I visited a traditional longhouse in Sarawak, East Malaysia, a shared place that functioned as both a home and workplace, for many. Neolithic long houses in Europe date from at least as early as 5000 to 6000 BC, and longhouses existed, and many still exist, in cultures around the world.

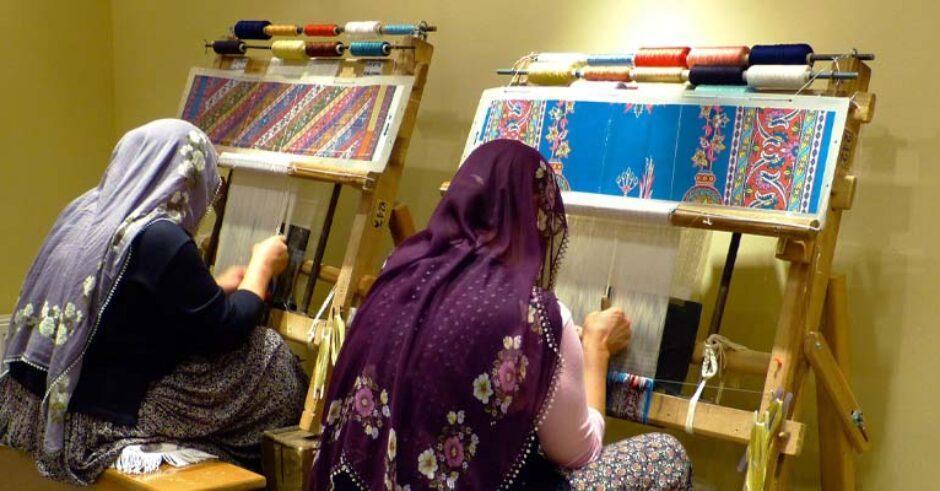

In medieval Europe the growth of individual craftsmen, merchants and skilled workers living in towns resulted in the creation of guilds, providing regulations for specific areas of specialisations and markets. The role of guilds were regulating working conditions, quality and market standards, for their members.

Craft guilds reached their peak prosperity in the 14th century, but started to disappear as industrial systems emerged as “the master-journeyman-apprentice relationship gave way to an employer-employee arrangement“. The modernisation of trade and industry during the industrial revolution being the death knell for most guilds.

It’s important to note that guilds

” were more like cartels than they were like trade unions“, ” a set of self-employed skilled craftsmen with ownership and control over the materials and tools they needed to produce their goods”.

And guilds weren’t without their problems,

“the evidence is that a common theme underlies guilds’ activities: guilds tended to do what was best for guild members. In some cases, what guilds did brought certain benefits for the broader public. But overall, the actions guilds took mainly had the effect of protecting and enriching their members at the expense of consumers and nonmembers …”

Global companies

The East India Company (EIC), founded in 1600, was a large, geographically distributed organisation.

Its’ prosperity fueled by monopolies, “the joint-stock company more generally, was Adam Smith’s prime example of precisely the sort of anachronistic and misguided forms of ancien régime capital organization that prevented economic growth and produced mismanagement and abuse, ranging from financial corruption to territorial conquest.

This is especially the case as more and more we see how ethereal and elusive corporations can be, shifting national allegiance and residence with ease.”

What has always worked

There’s very human, social, ethical, moral and wellbeing lessons related to work practices we can heed, in the age of digital work and workplaces.

Community, local connections and local leadership

Longhouses and guilds brought local craftsmen together, providing both practical and social support and connections, with their neighbours, peers and communities. A stark contrast to big city offices, whose occupants commute from numerous surrounding locales, and whilst often a member of multiple teams and networks at work, they don’t always include neighbours.

In We Need Both Networks and Communities, Henry Mintzberg, highlights,

“A century or two ago, the word community “seemed to connote a specific group of people, from a particular patch of earth, who knew and judged and kept an eye on one another, who shared habits and history and memories, and could at times be persuaded to act as a whole on behalf of a part.”

“In contrast, the word has now become fashionable to describe what are really networks, as in the

“business community”—”people with common interests [but] not common values, history, or memory.” The heart of enterprise remains rooted in personal collaborative relationships, albeit networked by the new information technologies.

Thus, in localities and organizations, across societies and around the globe, beware of “networked individualism“ where people communicate readily while struggling to collaborate.

An electronic device puts us in touch with a keyboard, that’s all.

The new digital technologies, wonderful as they are in enhancing communication, can have a negative effect on collaboration unless they are carefully managed.”

Exacerbating the well researched and documented issues of isolation, loneliness, digital and information overload, distractions, burnout, work overload, lack of emotional and practical support, decreased productivity, and decreased collaboration for many remote workers, is being a member of multiple teams.

Today’s prevalence of multiple team membership (MTM), also referred to as multi-teaming, involves teams crossing intra-organisational, geographical and organisational boundaries, with global, virtual and multi-organisational teams. Knowledge workers are members of four different teams, on average, creating the following challenges,

Increasing the number of members shared by different teams, also increases co-ordination and overhead costs, reducing the productivity benefits of MTM.

Weakened relationships and coherence within teams and projects, if time isn’t spent on personal interactions that develop trust and familiarity, and enable new members to understand every team’s unique context.

As the ratio of shared team members increases. so too do. conflicting demands and priorities, creating over committed and overloaded employees, with projects more frequently missing out on requisite work effort, knowledge and expertise for activities, reducing the quality and capability benefits of MTM.

Of those Australian organisations implementing a digital workplace without any other supporting non-digital workplace practices, only 13% reported productivity improvements. Compared to almost three times the productivity outcomes for those that did.

Importantly, these successful changes focussed on new management and reporting structures, new social connectivity, physical and emotional health initiatives, and additional staff pastoral care.

What this can look like in practice for remote workers

What ‘local’ means

Maybe your manager isn’t a neighbour, but they’re part of your broader, local community. They have empathy for localised conditions impacting remote work e.g. cultural, social, government laws and policies, economic, geographic, and infrastructure (internet and other).

Working and living locally, can mean hybrid working isn’t working partially at home, and partially commuting to a large, centralised office. It’s about social connectivity, so it can also mean being able to work alongside those fellow colleagues who are also neighbours, at small, satellite company workspaces and offices. This also benefits the local communities where workers live, through greater spend for local businesses, and reduced work commutes.

It can also mean expanding your ‘community’ to being team members, work friendships and neighbours. The benefits of work friendships is well established, and these friendships don’t need to be a team member, or someone working in your same division or location. Even when ‘work friends’ end up working for different employers, the practical, social and emotional benefits of this relationship can continue.

What this means in practice, is managers scheduling zoom coffee and lunch breaks for teams, are entirely missing the point, that we choose whom we seek practical, emotional, mental and social support from, just as we choose our close work friends.

A much better practice for creating a sense of community and belonging for teams, is ensuring every team meeting and interaction, starts and finishes with purely social, emotional, personal and non-work related conversations, to deepen connections.

“The best meetings are a group improvisation, a chance for co-creation. But, just like improvisers on stage, they need to warm up to get in the creative spirit. Neuroscience tells us that to do this well, people must feel welcome and connect with one another.

Even just five minutes speaking freely in gallery view on virtual calls — before you start sharing any slides — can change the entire dynamic of a meeting. Provide a lightly structured activity that allows each person a chance to speak. ”

Or it can mean working at a ‘Hoffice’, a Swedish invention, where random workers and freelancers living in the neighbourhood, show up at someone’s home – an available ‘Hoffice’ – to work as a group.

“Everyone in the [Hoffice] group works in 45-minute shifts, based on research suggesting people can’t concentrate for more than 40 minutes at a time. When the shift ends, an alarm clock buzzes, and the group takes a short break to exercise or meditate. Before starting again, everyone explains what they hope to get done, to add a little social pressure to actually accomplish something.

I think there is an inexpressible sense of community and the joy of getting things done [in Hoffice sessions] that might not happen at a co-working space or café.”

Loneliness is not just “feeling ignored, unseen or uncared for by those with whom we interact on a regular basis . . . It’s also about feeling unsupported and uncared for by our fellow citizens, our employers, our community, our government.”

History tells us, the success of nomadic, and also skilled workers working on one’s own, is community, not disconnection or working in isolation.

Yet ‘digital nomads’ and ‘digital workers’ – the self-employed and employees – continue to be stereotyped as working in isolation from home, or from soulless, commercial co-working spaces.

Tyranny of management, not distance

The tyranny of distance for remote workers, home based workers, and distributed teams, isn’t the distance, it’s the tyranny. Research has shown some unfortunate management trends during Covid-19 related remote working, of increasing in levels of distrust in employees, unreasonableness, surveillance, inflexibility, micromanagement, negligence and dispassion.

The success of managing digital workers, teams and work, isn’t the functionality of enabling technology or tools used, it’s the very human, ethical and moral choices managers make, reward, and therefore normalise, about their role and practices, including how technology is used.

In The Human Side of Management, Thomas Teal says “we make demands on managers that are nearly impossible to meet. For starters, we ask them to acquire a long list of more or less traditional management skills in finance, cost control, resource allocation, product development, marketing, manufacturing, technology, and a dozen other areas. In addition, we ask them to assume responsibility for organizational success, make a great deal of money, and share it generously.

One reason for the scarcity of managerial greatness is that in educating and training managers, we focus too much on technical proficiency and too little on character.

Managing is not a series of mechanical tasks but a set of human interactions.”

Medieval craft guilds provided mentoring for skilled workers, just as today’s coaches of elite sports teams delegate most skill training, including fitness, to specialist trainers and assistant coaches. The captain or skipper of sports teams isn’t the most technically skilled, rather the one best equipped to lead and inspire, and in the best position to make decisions in the big moments. Sponsors also play a significant role in successful sporting professionals.

In the age of rapid changes and ambiguity many see the evolution of middle management roles as critical for organisations to not only survive, but thrive.

How Automation Will Rescue Middle Management views automation as liberating human managers from mundane and routine tasks, to use capabilities that AI can’t replace. Emotional intelligence to engage and support employees through today’s relentless change, and ‘set employees free to create, innovate and inspire one another.’

What this can look like in practice for remote workers

The successful work practices changes of new management and reporting structures implemented by Australian organisations supporting the use of digital tools for remote workers, can be moving away from a ‘manager as coach, mentor, sponsor, leader and line / people manager – the popular, yet impossible, ‘all things to employees management’ model.

To a more supportive, practical, and healthier model, that enriches the manager-worker relationship on a more personal level, that includes greater pastoral care.

It takes a village to support healthy and thriving humans, including adults at work.

Line managers can, and should be, a full-time people management role. The real ‘People and Culture’ cultivators in organisations, choosing the right people for the role, and providing them with the right training, coaching and resources, line managers can successfully bridge communication, engagement, social and emotional gaps, for remote workers and workforces.

Especially if, like the local leaders of human outposts throughout history, there is a unifying sense of organisational purpose and mission. But managers are empowered to evolve their team sub-cultures, to best support the unique needs of the organisation’s many localised, micro communities, in ways that still achieves the purpose and mission of the whole collective.

Space

Digital workplaces also aren’t just about place, they’re very much about creating space. Not physical space, but cognitive, emotional, and social space.

Lack of this kind of space, is also exacerbating isolation, loneliness, digital and information overload, distractions, burnout, cognitive overload, lack of emotional support, decreased productivity, and decreased collaboration for many remote workers.

Adapting digital technology to human needs, not forcing humans to adapt to the technology.

What creating space can look like in practice for remote workers

Design meetings, communication, and work practices to provide:

- adequate individual reflection and thinking time, as our first ideas usually aren’t our best,

- adequate discussion time, means it doesn’t need to happen once, in one long meeting, but can happen via more effective short bursts over time, as successful remote teams communicate in bursts,

- adequate time to collaborate on doing things differently / innovative solutions, before a final version of a solution is presented for feedback / approval, and

- spaces for supporting all the dimensions of wellbeing, including personal relationships.

Improvement opportunities include:

- Use digital tools to enable transparency of documents that are works in progress, enabling relevant team members to collaborate on outcomes, before they’re finalised.

- More deliberate use of which technology is used, acknowledging the pros and cons, of video and audio tools. For large groups, use video to show relevant screens of documents to talk through, can be more effective and efficient, than showing a wall of people’s faces, or even one enlarged face, which impedes empathy.

- Understanding when emotional and social nuances are important in interactions, and using the appropriate technology to facilitate it.

Flow

Optimal working environments are safe, promote all areas of human wellbeing (physical, mental, social, emotional, purpose, family / community, and financial), that also includes enabling a mental state of ‘flow’, critical for non-repetitive activities and knowledge work.

Lack of disruptions and distractions, together with autonomy and control, are two ingredients necessary for knowledge workers achieving a state of flow.

Multi-tasking and task switching, are enemies of flow, as are unhealthy levels of stress, anxiety and burnout.

Healthy level of stress, that are moderate work demands and moderately challenging tasks – (eustress) – can be positive stress, than enhances flow.

“Optimal performance requires a degree of disciplined concentration. This complete focus is possible only when our consciousness is well ordered and our thoughts, intentions, feelings, and all the senses are focused on the same goal. This experience of harmony can be achieved by establishing control over attention (Csíkszentmihályi, 1990).“

What enabling flow can look like in practice for remote workers

Deliberate choices and protocols about the use of synchronous and asynchronous communications and interactions.

- When are people required to be ‘always on / always available’ versus self-management of when they take breaks, and are unavailable due to doing focussed work without disruptions?

- Are people able to control their availability, through the use of their calendars, switching off phones, auto-replies, etc.?

- Are there protocols about when emails are sent, to whom, and why?

- When is picking up the phone, a better choice than emailing, texting or instant messaging?

- How are you using digital technologies to balance synchronous and asynchronous communication and collaboration?

- Are the meetings that used to occur when everyone was on onsite, still appropriate – time, agenda and implementation – for hybrid team meetings?

- Are managers constantly recognising and acknowledging the value of remote work to the organisation’s purpose, to counter feelings of apathy and boredom?

Diversity and inclusion

The reality is for very individual and personal reasons, although their role maybe suitable for working from home, there will always be people who shouldn’t be required to do so, and some, for whom working 100% from home maybe ideal.

A recent Australian Centre for Future Work report found only 77% of those working at home, indicated their workspace at home was appropriate and safe. An Australian Institute of Criminology survey found the outcome of victims and offenders spending more time together, and other factors created by Covid-19 social distancing rules, resulted in coercive control abuse increased in frequency or severity for 47% of women who had experienced it previously.

Why the Australian Fair Work Commission recommends that working from home should be optional. Which makes the case for organisations providing locally available, digital workplaces for workers, some small satellite workspaces that build community and social connections and support, for co-workers living and working in the same neighbourhood.

Responsibilities for ‘inclusion and diversity’ also include neurodiversity, and within this concept, there is no normal, to which work and workplaces, should be designed. This encompasses dyslexia, ADHD and dyspraxia, as well as introversion and extroversion. Inclusion must also recognise that each person’s home context is unique, and deeply personal.

- When it comes to being on the introversion / extroversion spectrum, ~33% are on each end of the spectrum, with ~33% in the middle. Open plan offices, and large group gatherings – physical or virtual – is exhausting for those at the introversion end of the spectrum. Just as working in isolation – physical or virtual – is energy depleting for those on the extraversion end of the spectrum.

- A recent report by SAP ANZ found 1 in 4 of those working from home, did not have a computer desk, had internet network connectivity problems, and had limited private space, and 1 in 5 said they did not have an external monitor. Others reported being caregivers for elderly parents with dementia, meant keeping their cameras switched off, and being on mute during virtual meetings. Whilst others were embarrassed by their working circumstances at home, using fake backgrounds, or remaining on mute, due to background noise.

Quoting Anthropologist Dave Cook,

“in March, I published findings from a four-year research study tracking remote workers. I warned, to be a successful remote worker deep reserves of self-discipline were required, otherwise burnout followed.”

Quoting Michael Fenlon, the chief people officer at PwC, the company

“asked all of our teams to create well-being plans using the framework of mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual well-being, where spiritual refers to having a sense of purpose. We provided tools and examples and asked everyone on the team to have both a personal goal and a team goal. We asked teams to visit progress against those plans on a regular basis. And we asked all of our leaders to lead from the front, to share goals they’re working on, and to serve as role models.”

Recent research by Deloitte in the UK found that the highest return on investment were mental health initiatives and interventions that were personalised – achieving between 8 – 10 pounds ROI for every pound spent.

I’ve been using psychosocial assessments with my clients, whom have been working from home, and as part of hybrid working models, to identify their unique psychosocial needs – met and unmet. So as PWC has endeavoured to achieve, every individual has an appropriate and safe, and therefore, productive working from home and hybrid working, experience.

This provides vital insights for their managers and team members, to be able to respect individual needs and preferences, when adopting hybrid working models. Through very deliberate, and disciplined choices made by everyone, when it comes to associated workplace practices.

———————————-