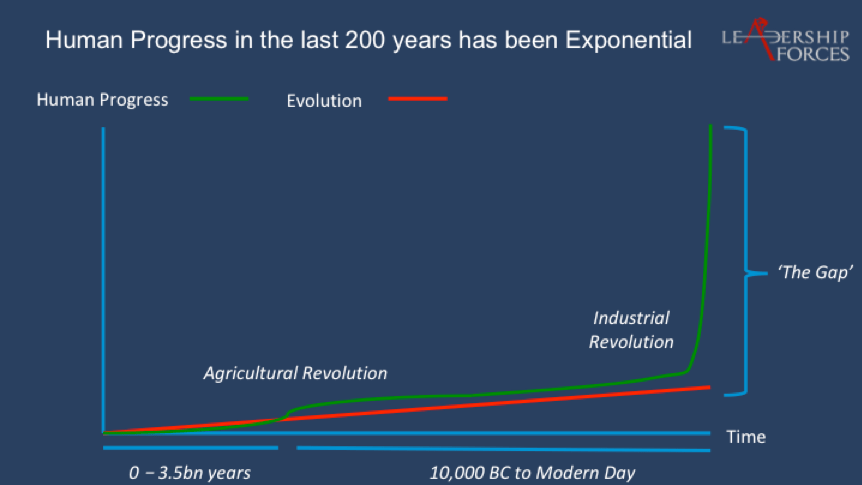

This is the second article in a series that attempts to explain ‘why we have a resilience problem’. In my last article, I wrote about how we are designed for a world that we no longer inhabit, looking at the slow process of human evolution and the impact that the last 200 years have had on our physical health. The following graph explains the gap between the world we are designed for and the one we inhabit.

Our rate of evolution has not caught up with our rate of progress.

This has impacted us physically, as explored in my previous article, but it has also impacted us mentally. Our brains evolve at the same rate as our bodies, so there is a significant part of our brain that has not evolved to meet the demands of the modern world.

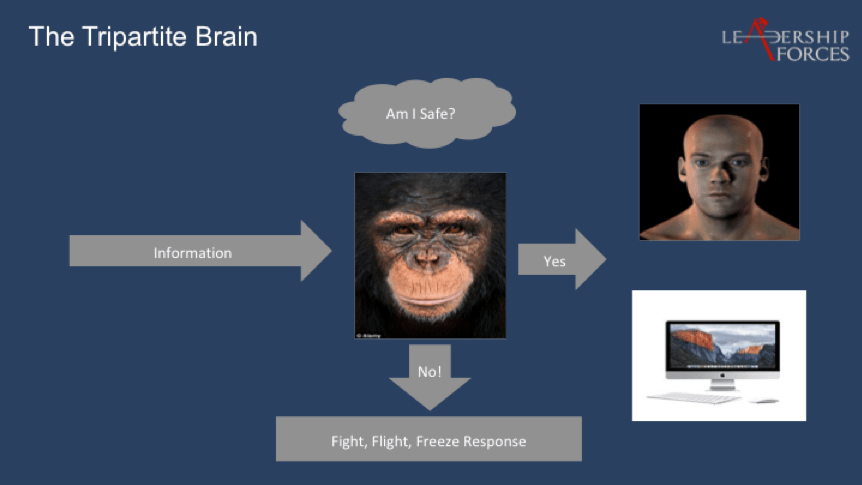

In the Chimp Paradox, Dr Steve Peters uses the metaphor of a Chimp to explain a complicated psychological model known as the Tripartite Brain. He explains that the human brain is actually composed of three separate ‘brains’ that sometimes work well together but often don’t.

- The Chimp brain is the part of the brain that controls your primal instincts. It controls your ability to fight, flight, freeze, feed and fornicate. The Chimp brain has evolved over billions of years and is largely focused on survival and reproduction.

- The human brain is the one we use when we are employing logic and reason. It is able to solve complex problems, understands data and considers the long-term impact of our behavior. When you’re planning an event, writing a business case or working quietly, chances are that you are employing your human brain.

- The computer is where your ‘mental models’ and ‘autopilots’ are stored. Dr Peters breaks these down further but I want to keep this article short so won’t go into more detail. The computer stores your knowledge for how to iron a shirt, drive a car and make a cup of tea. None of these things require complex thought; you can do these tasks while you have a conversation with someone. If you know how to do something, the information is stored in your ‘computer’.

The computer and the human brain can happily work together. As I am writing this article, I can think about what I want to say but I don’t have to think about how to type. My human and computer brains are working in parallel.

The Chimp sits quietly, observing all the information that I am taking in. Again, this is a simplified view but he is asking one question, ‘Am I safe?’

The moment he feels under threat, he hijacks the controls of the brain and takes over, firing a stress response that releases adrenaline. When you think about it from an evolutionary context, it makes sense. His ability to sense danger and respond appropriately has kept your ancestors (including your chimp ancestors) safe for long enough to reproduce and pass on their genetic code. Survival and reproduction are his priorities; he’s always on the look out for the sabre tooth tiger so he can protect you.

The problem is that the sabre-tooth tiger no longer exists and most of the ‘threats’ we deal with are perceived as threats, not actual threats. He’s kept your ancestors alive but in the modern world, he can create problems for you.

Let me give you an example. You are driving down the motorway and someone cuts you off before slamming on the brakes and taking the next exit. It’s a dangerous and stupid thing to do. You might be having a conversation with the person next to you about something relatively complex but as soon as this person cuts you off, you have to hit the brakes.

What happens? Chances are, you’ll feel the adrenaline pump through your system as you swear and hit the brakes. That reaction takes milliseconds but it is the perfect example of the chimp taking over. He’s been watching what’s going on and the answer to the question, ‘Am I safe?’ has suddenly become ‘No!’ so he takes control. He’s the one reacting causing you to swear and get aggravated because he is pumping your system full of adrenaline and preparing you to deal with a threat.

This is the same response you have if someone sends you an aggressive email or loses their temper in the office. The chimp brain detects a threat and responds by flooding the body with adrenaline. Most of the time, this approach isn’t helpful and you later regret it.

The chimp is very strong. He is stronger than the human, which is why he can always take control. Dr Peters’ book explains that you have to learn to manage your chimp and offers some techniques in his book.

Whenever you behave in a way that you later regret, chances are that your chimp has taken control.

When you’re about to order lunch and you have the best intentions of ordering a salad, at the last moment, you tell the waiter that you want ‘the fish and chips’… This is an example of the chimp hijacking you. I know because it’s happened to me many times!

The chimp brain wants you to preserve calories. He wants you to eat loads and avoid exercise. He has been developed over millions of years where food scarcity was a problem and often meant death. He will eat as much as possible and avoid exercise to burn calories because in a time of food scarcity, excess calories and fat were extremely valuable.

In the modern western world, this isn’t as much of a problem but the chimp has not evolved to understand that. He will hijack you to order the high calorie alternative to the healthy option. He is partly responsible for the obesity epidemic but not entirely because he can be managed.

If you get that sense that you’re going to be hijacked by the chimp when you’re about to order some food, manage him by saying to yourself, ‘it’s okay, you’re not going to be hungry, we’ve got a healthy snack in our bag. We can eat a light lunch and we’ll be fine’.

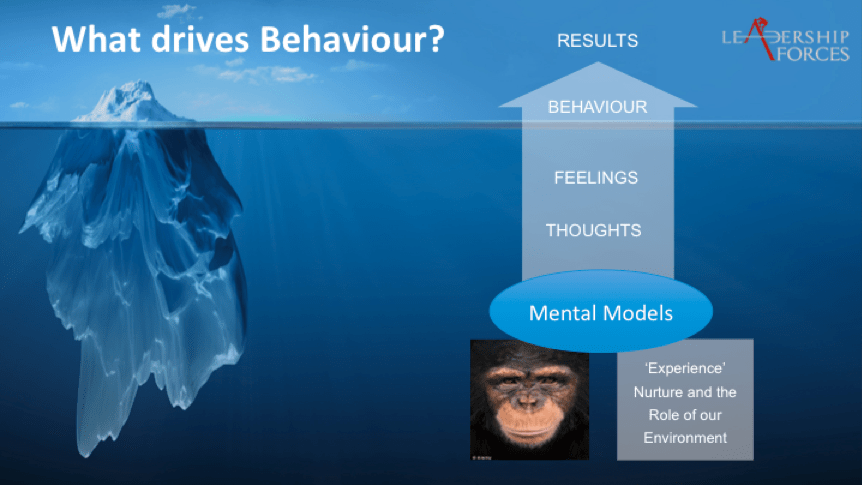

The chimp, human and computer explain how our brains were designed. They explain the role of nature and the impact it plays in the modern world.

The design of the brain and the role it plays can help to explain an enormous number of problems that we face in the modern world. One of the reasons that women on average are more likely to suffer from anxiety is because men and women’s chimp brains are wired slightly differently.

Women have traditionally been responsible for the raising of children. The female chimps and early humans that were anxious about their young tended to have more children that survived. Over millions of years of natural selection, this behavior compounds until it becomes an ‘evolutionary program’. It’s no longer as useful but it’s still there, running in the background of the female brain.

Men are able to very accurately assess the physical strength of other men. In David Buss’ book, ‘Evolutionary Psychology’ he explains how men have evolved to make very quick assessments of whether they can physically overcome another man. More often than not, those intuitive assessments are accurate. Again, when you think about the historical role of men, it makes complete sense that we would have been optimized to assess the physical capacity of other males.

The role that nature (evolution) and nurture (environment) play in shaping human behaviour is complex. Our experience and the evolutionary programs work together to shape our mental models and behaviour. The following picture outlines what you see (results and behaviour) and how things that go on beneath the surface drive it.

It isn’t easy to separate the two and explain which one is responsible for a specific human behaviour; it’s not quite as simple as that. However, we can look at common fears that humans share in cultures around the world because this takes the environment out of the equation.

Most children under the age of five are scared of the dark… Why? Well, when you apply an evolutionary lens to the problem, it makes sense. Humans interpret the world around them primarily through their eyesight. We have the second best eyesight to birds of prey. In the dark, our primary sense is useless giving predators an advantage. The chimp children that avoided the dark tended to survive. Again, that compounds over many years to become an evolutionary program that still runs today. It is why my daughter used to sleep with a night-light. Her chimp brain is telling her that she needs to be scared of the dark when in reality, that’s not true.

Humans are also scared of snakes and spiders across cultures. In the UK, from a logical perspective, this doesn’t make sense as we don’t have many dangerous snakes or spiders. But what would happen if I walked towards a group of people sitting together and threw a bucket of large but harmless spiders over them? No amount of logic and reasoning would change the likely reaction I would get. It would be pandemonium as their chimp brains take over and respond to the perceived threat.

This is also why we’ve learned to be fearful of heights. Heights carry a risk of falling that brings death.

None of this is insurmountable.

People climb mountains and handle dangerous animals because they have learnt to control their inner chimp brains. They’ve exposed themselves to their fears developing coping strategies to overcome them.

Many people struggle with behaviour that leads them to results that they don’t want. This has an impact on our ability to be resilient in the face of pressure. Understanding how the brain was designed and the role it plays in your daily life is essential to learning how to effectively ‘manage yourself’ and cope in the modern world.

In my next article, I am going to talk about the role of the environment and how your background and childhood has an impact on your resilience in the modern world.

This article is exclusive to The Business Transformation Network.

In case you missed it, you can read Part 1 of the series here.