Risk Management is fundamental to both project management and programme management, however it does not need to be complicated. This is a guide to risk management for people who want to start to manage risk effectively. This guide is targeted at people who are familiar with project management, PMO offices or risk management.

This article assumes that you have read our Beginners Guide to Risk Management article which has covered what a risk is, risk probability, impact and exposure and introduced the concept of RAID and Risk Registers.

Risk Mitigation

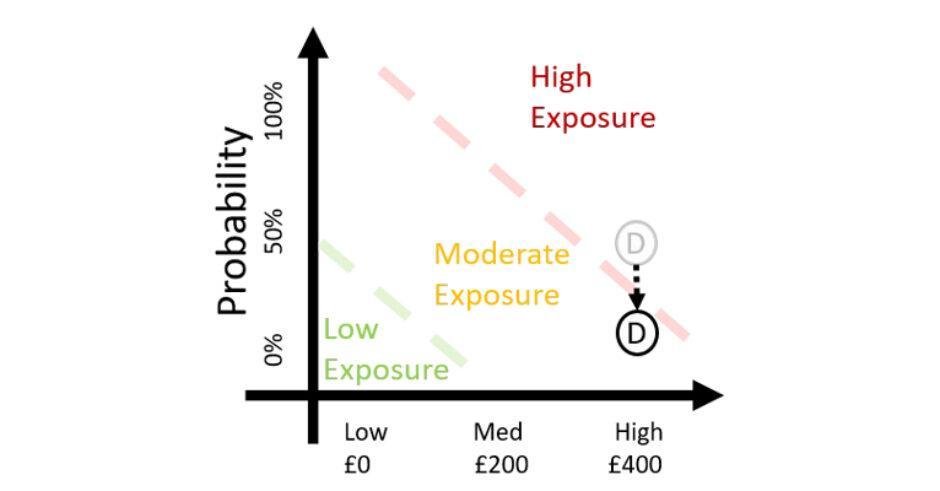

In the last article we identified and captured a number of risks. One of these risks was titled Risk D – ‘There is a risk that I miss a week of work due to pneumonia caused by rain’. We had identified that the cost of a day of work was £80 and so a week off would cost £400. We also estimated the probability of this particular risk was 40%, leaving us with a risk exposure of £160 for this risk.

Risk Mitigation is action that we can undertake to reduce the exposure of a given risk. This could either be an action to reduce the probability of it occurring or an action to lessen the impact if it does.

Simple example of risk mitigation:

There is a 40% risk that I catch pneumonia caused by rain, which means I would miss a week of work, costing me £400. I therefore have a risk exposure of £160 (40% of £400).

To mitigate this, I will buy a rain coat which will cost me £50. This will reduce the chance that I get ill in the rain from 40% to 10%, meaning my risk exposure is reduced to £40.

In this example, buying a coat is the mitigation action. The risk has been mitigated which reduces the expected cost from £160 to £90 (£50 to buy a coat and £40 residual risk). We can see how this mitigation action has changed the risk exposure on our risk graph that we introduced in the previous article:

This covers the fundamentals of risk mitigation. You identify actions which can be taken to minimise the risk. However, you must also be cognisant that some mitigation actions may not be cost effective.

Extreme example of risk mitigation:

There is a 40% risk that I miss a week of work due to pneumonia caused by rain, which would cost me £400. I therefore have a risk exposure of £160 (40% of £400).

To mitigate this, I will buy a new car which will cost me £20,000. This will reduce the chance that I get ill in the rain from 40% to 0%, meaning my risk is completely eliminated and my exposure is reduced to £0.

In this instance it would have been much more effective to accept the risk rather than try to mitigate it by buying a car. There is a mini business case assessment which you need to do to determine if any given mitigation option is worth doing. In our extreme example, it would be better to buy a coat and have some residual risk and than to buy a car and eliminate the risk completely.

Risk Lifecycle

Risk is not something static. The Risk profile of a project is always changing and so there is a lifecycle that risks go through.

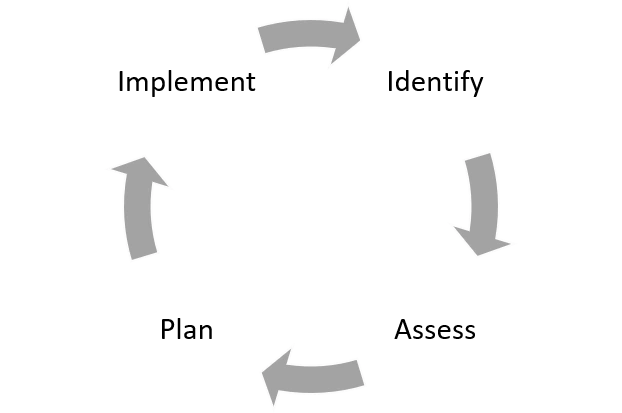

One commonly used risk lifecycle is:

- Identify – Identify that there is a risk

- Assess – Determine the Risk Exposure by defining the Probability and Impact

- Plan – Identify and plan the Risk Mitigation actions

- Implement – Implement the planned Risk Mitigation actions.

- Repeat the cycle – By completing Risk Mitigation actions you have changed the risk profile and so you should start the cycle again.

There is another key element that factors into Risk Management: time. The risk profile on one day may be different on the next as external factors may impact risk exposure.

Simple example:

Today… there is a 40% risk that I miss a week of work due to pneumonia caused by rain, which would cost me £400. I therefore have a risk exposure of £160 (40% of £400).

Tomorrow the weather forecast says there is no (0%) chance of rain so the risk exposure of that risk naturally reduces to £0 (0% of £400).

The above is a deliberately simple example, but to make it more business focussed…

If we run an e-commerce website which makes £10,000 per day, there is a 0.5% chance of a server crashing and our business has 10 servers running, there is a 5% risk of a server crash today (0.5% * 10 servers). We assume that any server crash causes a full outage and so we have a risk exposure of £500 per day (5% of £10,000).

If we are at capacity and so the server team adds a new server tomorrow, the risk probability increases to 5.5% (11 servers * 0.5% crash chance). We still assume that any server crash causes a full outage and so this means our risk exposure is now £550 (5.5% * £10,000).

The key point is that risk is not static. As risks are mitigated, the risk exposure reduces but likewise, new risks can be added or events can cause existing risk’s probability or impact to increase. Over time the profile of risk will change which is why you should continuously apply the risk lifecycle.

How to track the risk lifecycle in practice on a project?

The way that Project Management teams track and manage risk is using a Risk Register (sometimes part of a RAID log). This allows you to track and monitor risk on an ongoing basis, updating the risks as they change.

A risk register template could look like the below:

We introduced this template here but the additional columns in this which were not covered in the Beginners Guide are:

- Mitigation – This is the mitigation action to reduce the risk. It is entirely acceptable to accept the risk instead of mitigating it is the cost to mitigate outweighs the risk itself.

- Comments – This allows you to capture information about the risk at any given point in time. It also allows you to track updates, for example, ‘risk mitigation action complete, probability reduced from 50% to 25%’

- Last Update – This tracks the last time that the risk was updated. Different organisations have different policies for how regularly risks need to be reviewed. We find that at least every 2 weeks is a good general starting point, but this very much depends on the risk. Some risks may be related to specific time frames, such as risks associated with a cutover weekend and these may even need to be tracked hourly.

Risk Context

It is also important to know the context of the risk. The best way to think of the context is as the thing what would the risk impact if it occurred. A risk could impact on a variety of different things such as a project, a programme, a service or even an entire business.

Not all risks are related to you or your project and you should focus on those which are relevant to your context. Risks should be managed by the person accountable for the thing it affects (or someone that they choose to delegate to).

A simple example to demonstrate the point:

If you live in the United Kingdom, you would not consider the risk of it raining in the United States as it is not relevant to you (i.e. not .

As a more real example:

If you are running a project and you identified the risk above about the e-commerce servers failing, however… you do not work as part of that service, nor is your a project related to that service, you would not add that to your risk register.

You only add risks to your risk register that can impact on the outputs of your project. Instead you should contact the person that runs the e-commerce service and highlight the risk to them. In this example the risk is not in the context of your project and so it is not your to track.

This is important if your project is part of a programme. You could have a high impact risk which would not only affect your project, but also the entire programme. At that point it becomes a programme risk.

Likewise, if a risk on your project was likely to impact on the profitability of the organisation then it becomes a business risk. These risks need to be highlighted and escalated to the appropriate people as they affect a wider context than just your project.

Risk Tolerance

But, thinking about the above… doesn’t every risk on project affect the business that it is running in?

Yes, technically it does which is why we use Risk tolerance. This means that the business or programme that is governing the project decides on a level of risk (tolerance) that the project is able to manage.

Simple example:

Your programme manager might say “I want to be made aware of any risk that is:

- over 90% likely to occur (tolerance against probability) or

- has an impact of £10,000 or more (tolerance against impact) or

- has an exposure of £8,000 (tolerance against tolerance)”

If this was the case, you would be able to manage all risk in your project until it went over one of those tolerances and then you would need to escalate it to the programme manager.

Risk tolerance is used to ensure that people understand which risks they can manage and which must be raised up the chain. This risk tolerance is often closely linked to the risk appetite of an organisation.

More Advanced Risk Management

Risk Management is a complex topic. There are a range of topics that we have not covered such as:

- Risk Modelling

- Risk Categorisation

- When a Risk becomes an Issue (or anything related to Issue Management)

If you want to learn more then we would be happy to do an advanced guide. Please let us know by contacting us using our contact form.

If you need to revisit the Beginner’s Guide to Risk Management, you can view it here.

———————————-

Daniel Wright founded Monochrome Consultancy, specialising in Digital Transformation, IT Transformation and Project & Programme Delivery.

With his background in IT and InfoSec Dan is a techie at heart.

For more on Dan and/or Monochrome visit: www.monochromeconsultancy.co.uk