Being agile and adaptive in today’s age of ecosystems and accelerated change has seen a shift in what transformations of legacy organisations look like. Time to rethink what we mean, do and measure, when we talk business transformation.

Defining ‘ transformation’ in relation to strategies and initiatives

‘Transformation’ is one of the most commonly used words in organisations today, describing numerous types of strategies, projects and initiatives. Nine years ago in a university assignment for a Masters subject Management of Change, I acknowledged definitions of types of change in organisations that included Warren Burke and George Litwin denoting ‘first-order change’ that is incremental or transactional in nature, and ‘second-order change’ that is irreversible, radical and transformational in nature.

The absoluteness of transformational change reflected in McGreevey’s description of a successfully transformed organisation as one that has let go of and even forgotten, its historical self.

Walgreens moving from pharmacy retailing to treating chronic illnesses was a transformation that left the most of its past behind, and many argue its misleading to describe strategies and programs as transformational if they don’t achieve this. In What Do You Really Mean by Business “Transformation”? Scott Anthony posits operational changes – “doing what you are currently doing, better, faster, or cheaper”, that include digital initiatives that improve customer experience and satisfaction – is “playing an old game better”, is a company “sticking to its knitting” without reinvention and growth that is “transformational”.

Anthony also makes the following comments about core operating model transformations, “doing what you are currently doing in a fundamentally different way”, such as Netflix shifting from sending DVDs to streaming video content that now includes its own content, hasn’t altered customers turning to Netflix to be entertained and to discover new content, but the fundamental way Netflix is solving that problem has changed almost completely.”

Do the plethora of operational and operating model transformation strategies, programs and projects that don’t change the purpose of a company, deserve to be called transformations?

YES!! according to McKinsey in From disrupted to disruptor: Reinventing your business by transforming the core, because “the set of capabilities that are the core of a business are so intrinsic that any transformation that doesn’t address them will ultimately underwhelm and fizzle because the legacy organisation will inevitably exert a gravitational pull back to established practices.”

The Truth About Corporate Transformations provides evidence that getting a transformation off on the right foot required short-term success in improving performance and viability of the existing business. This developed a foundation of funding and capability for the longer term stages of transformation – those creating reinvention and growth of new revenues.

Anthony and others, including the authors of Two Routes to Resilience, recommend these operational and operating model strategies and programs form part of “Dual Transformations – a better way to manage a metamorphosis of organizations that enables shifting gears without falling apart.” Noting that “organizations built for legacy markets rarely pull off making a clean break from the past and turning into something entirely new. Innovative initiatives large enough to replace revenue lost to disruption can take years, and abandoning an old model can throw away any advantage it still has.”

Dual Transformations aren’t exactly new, Two Routes to Resilience point to IBM in the mid-1990s making changes to its mainframe business at the same time it set-up the separate and very successful Global Services organisation. Also, Apple reconceiving it’s PC business, whilst launching their new iPod and iTunes business.

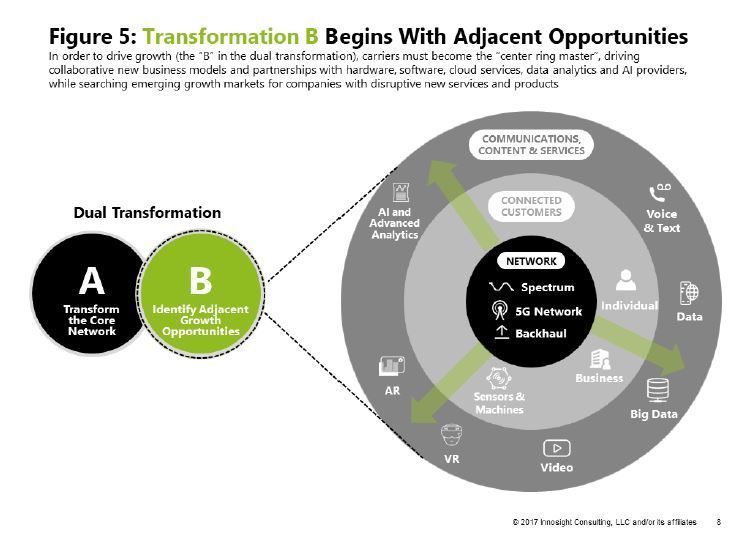

Historically discrete definitions of change – incremental versus transformational – is replaced with two synergistic transformation efforts happening in parallel, as depicted by Innosight in the following diagram.

Transformation A transforms the core business to be more sustainable and competitive through step changes to its operations and operating model.

Transformation B creates a separate, disruptive business to create the source of future growth, “without being encumbered by the legacy margins, revenue requirements and practices of the core business.”

Key to both is establishing a capabilities exchange, “a structure that allows the two organisations to live together and share strengths.”

Innosight also provides an example of dual transformation opportunities in telecommunications, where Transformation B leverages adjacent opportunities within its ecosystem.

Managing multiple, synergistic transformation efforts supporting business reinvention

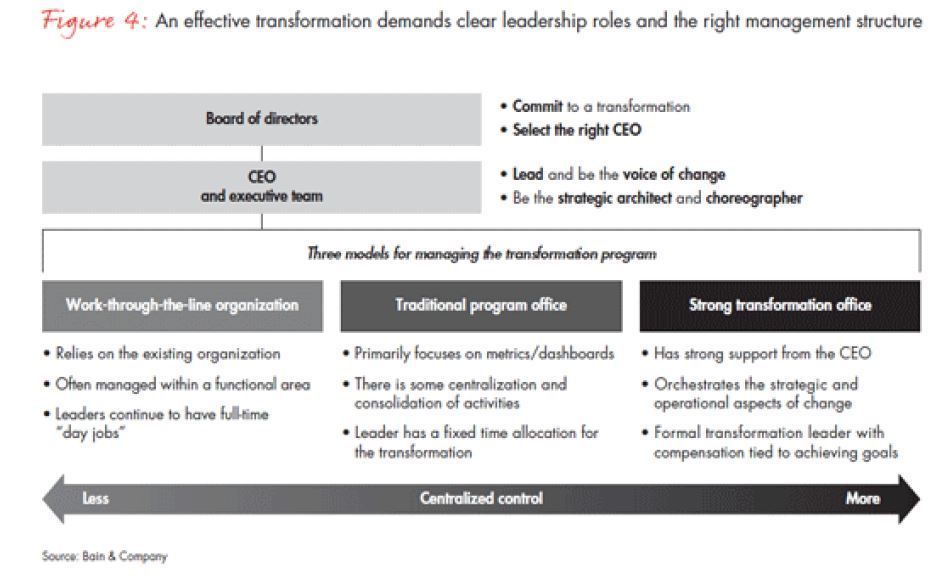

Bain & Company’s Choreographing a Full Potential Transformation also believe organisations need to understand the health of their existing business model, financial situation and market context, to address these capabilities first through incremental change. Additionally, they recommend that the choreography, scope, scale, interdependencies, complexity and cadence of business transformations, that involves disrupting the organisation itself, require a separate entity led by a highly skilled transformation executive – a Chief Transformation Officer (CTO) leading a Transformation Office.

So what do CTO’s do? McKinsey’s The role of the chief transformation officer describe it as independent from decisions of the past, fully integrated into the executive team but with the authority to hold other executives accountable.

The CTO is a high-level orchestrator of a complex process that involves large numbers of discrete initiatives that collectively contribute to the organisation’s transformation. Responsibility for making the day-to-day decisions and implementing those initiatives lies with line managers, but the CTO’s job is to make sure the job is done. This is not always easy.

PMO / ePMO versus a Transformation Management Office (TMO or TO)

Is This The Year of The Transformation Management Office? acknowledges the trend to refine portfolio management practices by integrating project deliverables with organisational strategy and value metrics. However, the level of disruption, experimentation, agility and pivots that transformations bring doesn’t sit well with the administration and compliance focus of PMOs. PMOs typically lack authority and capability to support the CTO in answering McKinsey’s eight questions in the previous diagram and be role models of the new behaviours associated with the transformation.

For Dual Transformations the CTO and TMO could orchestrate what Two Routes to Resilience identifies as giving Transformation B – the new disruptive organisation – a competitive advantage over independent start-ups, by sharing existing resources from the core. Managing the boundaries between the legacy and new business by ensuring exchanges of resources don’t impact business continuity of the core, also playing referee in any core leaders interfering in the disruptive division. The “who owns the customer”, “who pays for shared resources” type of squabbles.

Metrics that matter for transformations

PMO Status Reports aflame with red performance indicators for scope, time and budget might make a transformation initiative appear to be in serious trouble. When in reality some wrong turns, a lesson learnt and a pivot or two, actually has it on track to deliver greater value in ways not previously foreseen.

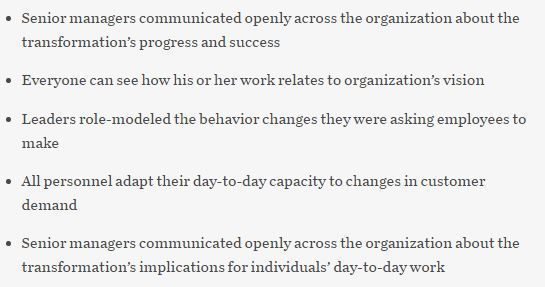

In addition to meeting business objectives IMA’s Implementing Organizational Changes at Speed stresses the importance of measuring the achievement of human objectives as part of a business transformation. McKinsey’s four years of research on organisational transformations in How to beat the transformation odds agrees, the 5 actions they found to correlate most with business transformation success are:

3 Digital Transformation Metrics That Work For Everyone also recommends continuously measuring where traction is being achieved during a transformation to provide insight into what’s working and what’s not, in addition to measuring long-term impact:

- Changing mindsets and adoption of new behaviours, and employee and business partner experience

- Speed to transform – consisting of a number of KPIs that serve as indicators of progress, including other operational or capability metrics such as task automation, quality metrics, productivity, digital application performance

- Customer experience

- Financial impact

Every transformation is hard work and brings their own unique challenges. I agree with How to beat the transformation odds there is no silver bullet, and today’s successful business transformations have a form quite different from the past. What hasn’t changed is that focussing on people and not the project, through having, developing and supporting the right leaders and people remains essential. As is continual communication from leaders who model new behaviours, tell an engaging and accurate story about what’s changing and why, whilst highlighting progress and success.